Saurabh Bhasin

Saurabh BhasinSaurabh Bhasin loved Delhi, the city where he was born.

Growing up, he longed for the winter months which offered a brief escape from the Indian capital’s long and harsh summers.

But over the years, his yearning for winters turned into fear. Air pollution increasingly crossed hazardous levels between October and January, leaving the city’s skyline hazy and air poisonous. Ordinary activities like walking outdoors or even playing with his child at home started feeling stressful and risky.

In 2015, Mr Bhasin, a corporate lawyer, filed a petition in the Supreme Court on behalf of his toddler – along with the fathers of two six-month-olds – seeking a ban on the use of firecrackers, which are burst mostly during festivals and weddings.

“The alarming rate of deterioration of the quality of air in Delhi due to air pollution [is] caused by, but not limited to, traffic congestion, dust from widespread construction, industrial pollution and the seasonal use of firecrackers,” his petition said.

The court issued guidelines to regulate the use of crackers but Delhi’s air continued to deteriorate.

In November 2022, Mr Bhasin’s daughter was diagnosed with asthma. Earlier this year, he and his family left for the coastal state of Goa, around 2,000km (1,242 miles) away, where they live now.

It’s not a choice available to millions in Delhi, who cannot leave their livelihoods and are forced to live through the smog.

But a small number of people who have the means are choosing to move out – either permanently or during winter.

Mr Bhasin is one of them.

“We know that bringing [his daughter] to Goa doesn’t mean her asthma will go away. But we are sure that had we kept her in Delhi, the chances of it getting worse would have been much higher,” he says.

Getty Images

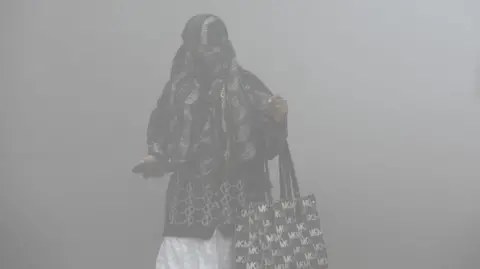

Getty ImagesHis concerns are not unfounded. Over the past few years, between October and January, Delhi’s air quality has frequently deteriorated to levels that the World Health Organization categorises as hazardous to health.

The Indian health ministry’s own recommendations say that poor to severe air quality may lead to an increase in morbidity and mortality among vulnerable sections such as children, elderly people and those with underlying medical conditions.

The recommendation advises people to avoid outdoor physical activities, and asks vulnerable people to remain inside and keep activity levels low when the air quality dips to levels classified as “severe”.

Mr Bhasin finds these measures cosmetic. “You can either invest in a solution now or keep putting a band-aid on it and pay the price for generations,” he says.

A 2022 study by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago found that air pollution can shorten the lives of people in Delhi by almost 10 years.

Rekha Mathur* is among those who have chosen to temporarily leave every year. In the winter, she relocates to the outskirts of Dehradun, near the Himalayan foothills.

She recently had a baby and now wants to stay away longer from Delhi, which struggles with bad air throughout the year. But her husband has to stay back for work, which means Ms Mathur is the child’s sole caregiver for months, and their son only gets to see his father occasionally.

“Our whole life is built around Delhi. I would have never left the city, if not for the worsening air pollution,” she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMs Mathur says she is unsure how long the arrangement can continue as her son grows up and needs regular schooling.

It worries her that pollution is not just restricted to urban centres like Delhi now, but even smaller, scenic cities like Dehradun.

In Delhi, the city she longs to return to, the crisis has been a matter of debate for years.

Over the past four decades, India’s Supreme Court has ordered the relocation of polluting industries, the conversion of commercial diesel vehicles into cleaner alternatives, the closure of brick kilns and the speedy construction of bypasses and expressways.

This winter, as smog returned to Delhi and adjoining regions, authorities imposed measures such as restricting non-essential construction, halting demolition activities, shutting down polluting industries, and limiting the number of vehicles on the road.

Yet, air quality hasn’t improved much. Residents express frustration that the onset of winter triggers an intense debate around air pollution every year, but hardly yields results.

Journalist and writer Om Thanvi, who lived in Delhi for more than 15 years, says there is no magic wand but to find a viable solution, the government must treat this as a public health emergency.

Mr Thanvi moved to the western state of Rajasthan in 2018 to teach, planning to return soon. But now, he says, he has decided to stay there permanently.

“I had to use an inhaler in Delhi. But since I have moved here, I don’t even remember where it is,” he says.

He advises others who have the means to leave the city until things improve.

“I miss Delhi’s vibrant cultural scene, but I don’t regret leaving and I don’t plan to return.”

But for millions of Indians, this is not a choice.

Sarita Devi migrated to Delhi from Patna city years ago for work. She irons clothes for a living, spending hours outdoors with her cart through winter and summer.

“I can’t go back to Patna because I can’t earn money there. And even if I did go, it wouldn’t change much for me,” Ms Devi says.

“I visited for a festival a few days ago and the air there was equally hazy,” she adds, highlighting the fact that the air in many north Indian cities is highly polluted.

Mr Bhasin says that when they moved to Goa in June, leaving behind friends and family was particularly difficult.

But now, he is confident that the decision was right.

“We are no longer willing to pay the price with our child’s health.”

*Name changed to protect privacy

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook