On Jan. 7, the phones of immigration advocates in Bakersfield began lighting up with calls from immigrant farmworkers. The messages said the U.S. Border Patrol was conducting an indiscriminate dragnet in the area, pulling over vehicles presumed to be carrying immigrants to work and taking dozens into custody.

To the advocates, this didn’t seem right. The Border Patrol — a unit of U.S. Customs and Border Protection — had not been seen operating in anyone’s memory in Bakersfield, some 300 miles from the patrol’s California offices in El Centro, a few miles from the Mexican border.

Although there are two detention centers in Bakersfield run by ICE — Immigration and Customs Enforcement — none of the detainees could be found in either one. The Border Patrol, a sister agency of ICE, staged its raids not at ICE installations, but out of a parking lot at a facility of the Interior Department, which has nothing to do with immigration or border security.

There’s a lot of fear, a lot of anxiety for everyone with an undocumented loved one, which is a significant portion of the Latino community in Kern County.

— Antonio De Loera-Brust, UFW

The Border Patrol eventually asserted that it had conducted a four-day “targeted enforcement” operation aimed at undocumented immigrants with criminal records, ultimately detaining 78 individuals mostly for crimes such as drug trafficking, burglary and child abuse.

It’s fair to say that almost no one familiar with the immigration ecosystem in Kern County, where Bakersfield is located — not immigration lawyers, United Farm Workers officials or employers — believes a word of this. The UFW and other sources estimate that some 200 people were detained in just the first two days, and 1,000 in all may have been detained and released.

Newsletter

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Rather than “targeted” enforcement, the Border Patrol conducted “random stops of vehicles exclusively founded on racial profiling of individuals,” Ambar Tovar, director of legal services for the UFW Foundation, told me.

The officers raid locations where they knew they would find farmworkers gathering — such as at a Home Depot, where immigrant laborers come to seek day work, and along California Route 99, the highway traveled by immigrant farmworkers heading to their jobs. At some spots, where they were asked to show warrants naming targeted individuals, the officers simply drove away without answering.

“They definitely seemed to be targeting agricultural workers and day laborers,” said Casey Creamer, president of California Citrus Mutual, the trade association for citrus growers.

Creamer said there have been no indications that immigrants in Kern County were responsible for a wave of violent crime, the ostensible justification for the raids.

“The people who got targeted get up to go to work at 5 or 6 a.m.,” he said. “They work hard and then go home to their families. That’s incompatible with violent crime. Drug dealers aren’t going out to harvest citrus.”

One aspect of these raids elicits broad agreement: Their effect was to sow fear. “It’s had a very chilling effect on the whole community,” said Antonio De Loera-Brust, a spokesman for the UFW. “There’s a lot of fear, a lot of anxiety for everyone with an undocumented loved one, which is a significant portion of the Latino community in Kern County.”

Creamer estimates that about 25% of immigrant workers in the area stayed home from work in the first day of the raids, and 75% afterward. That continued until Jan. 10, when word spread that the Border Patrol had left the county and gone back to El Centro.

Until then, he said, “the raids sent shock waves through the entire Central Valley,” the breadbasket of California and of the entire country. At the Mercado Latino Tianguis outside Bakersfield, a popular shopping spot for the Latino community, customers all but disappeared during the raids and about one-third of the businesses closed.

The Border Patrol didn’t respond to my request for further information about the raids.

It’s hard to overestimate the impact that raids like these could have on California agriculture, which, like other states, is highly dependent on immigrant labor. The raids occurred as the harvesting of California oranges, mandarins and lemons was entering a peak period for fresh fruit. California accounts for about 90% of the domestic supply of oranges, mandarins, lemons and grapefruit.

About 20% of the estimated 24,000 citrus farm employees in California work in Kern County, Creamer says. In this case, he adds, the immediate impact was muted because the raids occurred over only four days and the schedule of citrus harvesting can be somewhat flexible.

Yet “in the small farming towns outside Bakersfield, at gas stations and in the miles and miles of fields, everyone seemed to know about the arrests,” my colleagues Rachel Uranga and Andrea Castillo reported, “sowing fear among migrant families, many of whom had children or spouses that were born here” and consequently are American citizens.

Pupils from immigrant families stayed home from school. About 1 million children in California — 10% of the school-age population — have least one undocumented immigrant parent and about 115,000 are themselves undocumented.

The Homeland Security Department hasn’t disclosed who authorized the raids and why they took place. Although they were launched before Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration, they impressed many as a harbinger of attacks on immigrants to come during his administration. They hint at Trump’s preoccupation with illegal immigration.

The raids caught the community’s elected representatives flat-footed.

“I have received numerous calls from constituents expressing fear for their families’ safety, and I do not support inciting concern,” Rep. David Valadao (R-Hanford), said in a statement issued the Monday after the raids ended. “We can all agree known criminals should be expelled from the United States, but it is crucial that future operations are communicated clearly to avoid causing any further alarm among our farmworkers.”

Gregory Bovino, chief of the Border Patrol’s El Centro sector, boasted on social media about what he called “Operation Return to Sender,” stating that 60 agents had been deployed in marked and unmarked vehicles. Bovino further asserted that his sector’s “responsibility” stretches from the Mexican border north to the California-Oregon state line.

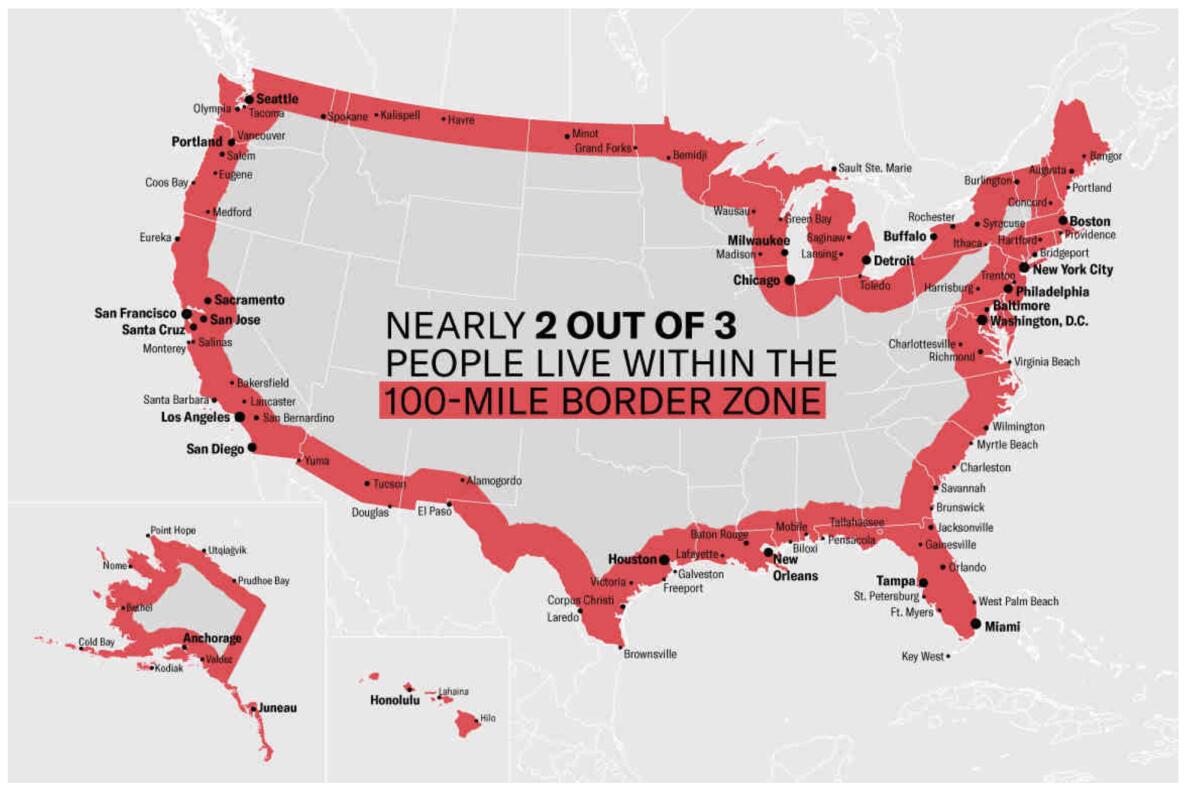

That’s true, up to a point. The Border Patrol claims the right to stage warrantless searches within 100 air miles of any external boundary of the U.S., including national boundaries and shorelines. That’s a zone in which two-thirds of the U.S. population lives, encompassing all of Florida, Hawaii, Maine, New Hampshire and Michigan; most of New York and more than half of California, including all its major cities.

The Border Patrol claims jurisdiction over more U.S. territory than most people know.

(ACLU)

What struck immigrant advocates about the raids was the sheer thuggishness of the operation, which dovetailed neatly with the uncompromosing rhetoric about immigration sounded by Trump during his campaign and in his inaugural speech Monday.

Agents transported detainees from Bakersfield to El Centro, a drive that can take as long as six hours, instead of processing them locally, where they would be available for local legal advice and representation. Detainees said they were released in El Centro without transportation home.

Two UFW members were pressured into signing a form attesting to their voluntary departure from the U.S., then shipped over the border from El Centro to Mexicali, De Loera-Brust says.

“That effectively waived their rights to a hearing or due process or legal representation, and allowed the Border Patrol to dump them in Mexicali,” he said. “At that point, there’s not much we can do. By the time we got our members a lawyer, they were already in Mexico and there was no case for our lawyers to argue.”

The union says neither individual had a criminal history or an outstanding criminal warrant. “They were undocumented, but they were otherwise completely law-abiding, hardworking folks, the primary breadwinners for their families, leaving behind undocumented spouses and U.S. citizen children who were born in this country,” De Loera-Brust said.

Agents in an unmarked car pulled over Ernesto Campos, the owner of a Bakersfield gardening service who was naturalized as a U.S. citizen more than 10 years ago. According to a video Campos shot on the scene and that was aired on Bakersfield TV station KGET, the agents demanded that Campos’ passenger, an undocumented employee step out of the truck. Campos informed them that the passenger already had an asylum hearing scheduled. Campos shut off his engine and gave the agents his driver’s license.

Nevertheless, according to an exchange captured on the video, an agent slashed Campos’ truck tires, which can be seen deflated on the video. When Campos asked why the agent had immobilized his vehicle, the agent replied, “I’m not going to argue with you, bro. You did what you did, I did what I did.” He verified that Campos was a U.S. citizen, but he was arrested on suspicion of “alien smuggling.” Campos was released about four hours later. The border Patrol didn’t respond to my request to identify the agent and explain his conduct.