BBC’s Center East analyst

Reuters

ReutersHistoric buildings in Mosul, together with church buildings and mosques, are being reopened following years of devastation ensuing from the Iraqi metropolis’s takeover by the extremist Islamic State (IS) group.

The venture, organised and funded by Unesco, started a 12 months after IS was defeated and pushed out of town, in northern Iraq, in 2017.

Unesco’s director-general Audrey Azoulay and Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani are attending a ceremony on Wednesday to mark the reopening.

Native artisans, residents and representatives of all of Mosul’s non secular communities will even be there.

In 2014, IS occupied Mosul, which for hundreds of years was seen as a logo of tolerance and co-existence between completely different non secular and ethnic communities in Iraq.

The group imposed its excessive ideology on town, focusing on minorities and killing opponents.

Three years later, a US-backed coalition in alliance with the Iraqi military and state-linked militias mounted an intense floor and air offensive to wrest town again from IS management. The bloodiest battles targeted on the Previous Metropolis, the place the group’s fighters made a final stand.

Mosul photographer Ali al-Baroodi remembers the horror that greeted him when he first entered the world shortly after the street-by-street battle was over in the summertime of 2017.

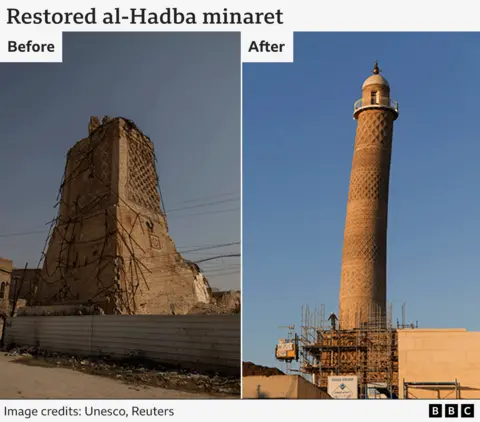

He noticed the gloriously skewed al-Hadba minaret, often known as the “hunchback”, which had been emblematic of Mosul for tons of of years, in ruins.

“It was like a ghost city,” he says. “Lifeless our bodies throughout, a sickening odor and horrible scenes of town and the skyline with out the Hadba minaret.

“It was not town that we knew – it was like a metamorphosis – that we by no means imagined not even in our worst nightmares. I fell silent after that for a few days. I misplaced my voice. I misplaced my thoughts.”

Eighty per cent of the Previous Metropolis of Mosul, on the west financial institution of the Tigris, was destroyed throughout IS’s three-year occupation.

It was not simply the church buildings, mosques and outdated homes that wanted to be repaired, but in addition the neighborhood spirit of those that had lived there for therefore lengthy in relative concord between religions and ethnicities.

The massive process of rebuilding started below the auspices of Unesco with a finances of $115m (£93m) that the company had managed to drum up, a lot of it from the United Arab Emirates and the European Union.

Father Olivier Poquillon – a Dominican priest – returned to Mosul to assist oversee the restoration of one of many key buildings, the convent of Notre-Dame de l’Heure, recognized domestically as al-Saa’a, which was based almost 200 years in the past.

“We began by attempting first to assemble the workforce – a workforce composed of individuals from Previous Mosul from completely different denominations – Christians, Muslims working all collectively,” he says.

Father Poquillon says that bringing the communities collectively was the most important problem and the most important achievement.

“If you wish to rebuild the buildings you’ve got obtained first to rebuild belief – if you happen to do not rebuild belief, it is ineffective to reconstruct the partitions of these buildings as a result of they are going to grow to be a goal for different communities.”

In command of all the venture – which included the restoration of 124 outdated homes and two particularly positive mansions – has been the chief architect Maria Rita Acetoso, who got here to Mosul straight from restoration work for Unesco in Afghanistan.

“This venture demonstrates that tradition can also create jobs, can encourage abilities growth and as well as could make these concerned really feel a part of one thing significant,” she says.

She hopes the reconstruction can restore hope and allow the restoration of individuals’s cultural id and reminiscence.

“I feel that is significantly vital for the younger generations rising up in a scenario of battle and political instability,” she provides.

Unesco says that greater than 1,300 native younger folks have been skilled up in conventional abilities, whereas some 6,000 new jobs have been created.

Greater than 100 school rooms have been renovated in Mosul. 1000’s of historic fragments have been recovered and catalogued from the rubble.

Among the many host of engineers concerned within the rebuilding, 30% have been ladies.

Eight years on, the bells are ringing out once more throughout Mosul from al-Tahera Church, whose roof collapsed after critical harm below IS occupation in 2017.

Different main landmarks of Mosul have additionally been restored – that wriggling minaret of al-Hadba, the Dominican al-Saa’a Convent and the complicated of Al-Nouri mosque.

And folks have been capable of return to the homes which have been residence to their households for hundreds of years.

One resident, Mustafa, stated: “My home was in-built 1864 – sadly it was partly destroyed throughout the liberation of Mosul and it was unsuitable to dwell there, particularly with my kids.

“So I made a decision to maneuver to my mother and father’ home. I used to be very happy and excited to see my home rebuilt once more.”

EPA

EPAAbdullah’s household has additionally lived in a home within the Previous Metropolis because the nineteenth Century when the world was a centre for the wool commerce – which is why he says their house is so valuable to them.

“After Unesco rebuilt my home, I got here again,” he says. “I can not describe the sensation I had as a result of after seeing all of the destruction that occurred there, I assumed I might by no means be capable to come again and dwell there once more.”

The scars of what the folks of Mosul endured are but to heal – simply as a lot of Iraq stays in a fragile state.

However the Previous Metropolis’s rebirth from the rubble represents hope for a greater future – as Ali al-Baroodi continues to doc the evolution of his beloved residence day-to-day.

“It is actually like seeing a useless individual coming again to life in a really, very lovely means – that’s the true spirit of town coming again to life,” he says.