Idit Negrin would try anything to beat the trauma haunting her since attending the Nova Music Festival on October 7th, when Hamas massacred hundreds of civilians. “We saw the terrorists, and they started shooting at us,” she said. She ran for her life.

Afterwards, “I woke up every night, every night around 3 o’clock screaming and sweating and shaking. I think after a day, or two days after, I felt that I’m falling down, crying.”

We met her this summer as she was two-thirds of the way through her 60-session course of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). It’s a treatment long used to combat compression sickness in divers, and wounds that will not heal. But at the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Research, in Be’er Ya’akov, Israel, they’re now also treating a very different malady: post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD.

Negrin described her experiences with PTSD: “You feel like you’re going crazy. I call people and scream, ‘There is a terror attack again!’ And then you understand that you have no control of your brain.”

Negrin is trying to regain that control, along with about 650 other October 7th survivors suffering from PTSD who are being treated, for free, alongside military veterans at the Sagol Center – currently the largest hyperbaric center worldwide.

CBS News

Dr. Shai Efrati runs this clinic, where they’re treating up to 350 patients a day, and are on the forefront of this sort of medicine. “What we are doing is actually tricking the body,” Efrati said. “Hypoxia, lack of oxygen, is the most powerful trigger to induce all the repair mechanism cascade.”

Efrati says they’re inducing repair mechanisms in the body and brain inside these pressurized chambers, where it feels like you’re scuba diving down to 30 feet. Patients breathe in pure oxygen, which under such high-pressure conditions the body can absorb at up to 16 times the normal level. Then, masks are removed for five-minute intervals.

Efrati said, “The decline from very high back to the normal is being interpreted at the similar level as hypoxia, as lack of oxygen. That causes the body to trigger the stem cells, and for the first time even in humans, we can see generation of new neurons, generation of new blood vessels in the brain. And this is mind-blowing.”

The treatment has been described as “unapproved” and “not proven.” “When we speak about hyperbaric oxygen therapy, this is how it should look like,” Efrati said.

“You’re saying there are a lot of frauds out there?” asked Doane.

“Indeed. And this is not only not good, it can be even dangerous.”

CBS News

Dr. Efrati is constantly experimenting with new ways to use this treatment. At his clinic near Tel Aviv, we got to see how they’re catering hyperbaric medicine to athletes (“If we can shorten the recovery period, you can push harder doing the exercises”), and helping patients with brain injuries regain movement through the growth of new neurons and blood vessels in the brain.

“It’s not that we are fixing his running,” Efrati said about one athlete’s performance. “We are fixing the brain.”

They’ve published several studies, looking at PTSD in veterans. One, out today, found that 68% of patients showed significant improvement. Another reported that PTSD remission lasted at least two years, which is higher than other established treatments. “We want to evaluate everything objectively,” said Efrati.

It’s conclusive enough for the Israel Defense Forces, or IDF, to ask Efrati’s team to stop testing and start treating. The doctor says that while you can always ask for more data, “You see the evidence in front of you.”

Shachar Mizrhai was one of those IDF veterans referred in 2018 for the initial clinical trial. He was a soldier during a 2014 Israeli offensive in Gaza and was in an armored vehicle when it was ambushed. In the short term, he was thinking about survival; the suffering came later. “I can’t sleep at night,” he said. “In the moment I put [on] the uniform, I feel like I want to die. I smell blood. I smell war.”

He’d tried drugs, therapy and sleeping pills. He contemplated suicide. “Nothing really helped to get back to life,” he said. “And I heard that this might be help, and maybe this is my last chance before I finish my life.”

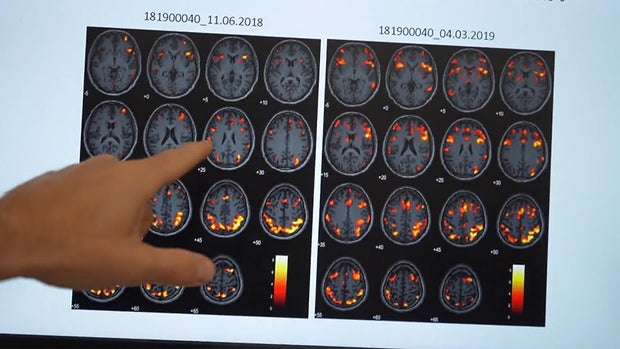

Dr. Keren Doenyas-Barak, who heads the PTSD program at the Sagol Center, followed Mizrhai through his 60 sessions, and showed us his brain scans from June 2018, and March 2019, highlighting activation of areas used to effectively regulate emotion, or process information. The later brain scan images were lighting up; that wasn’t happening before the treatment.

CBS News

“Many people tend to look at PTSD as a psychological phenomenon, not as a biological phenomenon,” Doenyas-Barak said. “So, we treat PTSD very similar to other brain conditions.”

For Mizrhai, the treatment changed everything:” “It’s the first time that I was feeling again. I begin to sleep at night, I was less afraid. It’s make me feel alive again. … I was a dying man, and after this, I’m a living man.”

North Carolina Republican Congressman and medical doctor Greg Murphy said, “If it’s being offered in Israel and they’re getting such good results, why the hell are we not offering it in the United States?”

That’s a question Murphy – a member of the House Committee on Veterans Affairs – is raising in the halls of Congress. One in 10 of his constituents is a veteran. “I love our VA,” he said. “But we’re not reaching a certain segment of our veterans if we’re having 22 commit suicide every day. And if we’re doing something and there is a treatment that has shown definitive results, I believe it’s medical malpractice not to offer that to our veterans.”

In 2023 he introduced the Veterans’ National Traumatic Injury Treatment Act. “We just basically want the VA to do a pilot study within their own confines to see whether they show that hyperbaric oxygen works or not,” he said.

And what is he hearing from the VA? “They just don’t want to do anything; it’s just hands up,” he said. “The reasons that we’ve heard is, ‘Well, the results are mixed.’ Fine. Look at the results in the last 15 years. Look at the studies in Israel. We are seeing an absolute effect in this, and other disorders, for Parkinson’s, migraines, some even MS, neurological disorders.”

“Sunday Morning” requested an interview with the Department of Veterans Affairs, but they declined to comment.

In Salt Lake City, Utah, we met Dr. Lin Weaver, who runs Hyperbaric Medicine at Intermountain Health. They treat about 20 patients a day, which puts into perspective the huge numbers – 350 daily – being treated in Israel. He says they use their hyperbaric chambers for PTSD patients rarely, because it is expensive, but he has seen positive results: “I’ve had patients that I’ve treated. Every one has got surprisingly better,” Weaver said.

But insurance companies say there is not enough proof it works for PTSD. And in the U.S., out-of-pocket costs soar above $50,000.

“What’s necessary is like a drug trial,” Weaver said. “But these trials take years to accomplish. It all rests with, ‘Is there an initiative? And is there a funding source?'”

Doane asked, “But if doctors like you feel so strongly that this works, why isn’t there enough push coming from folks like you to say, ‘Prove this’?”

“Well, believe me, we’ve tried,” Weaver replied. “I have submitted proposals to extramural funding agencies. So far, they haven’t accepted them.”

Doane asked Dr. Efrati, “You are out on the frontier here of medicine. Is there a danger in that?”

“As a scientist, I will always tell you I need more study, I need more data,” he replied. “But as a physician, when I’m sitting in front of you looking at your eyes, you have a problem now. This is our job as a physician.”

Idit Negrin says this treatment is giving her hope she can move past that nightmare at the Nova Music Festival. She hopes, with the therapy, she can move on with her life.

But she wears a reminder – a Nova necklace – while she gets treatment. “I don’t get her off my neck,” she said.

Her progress is motivation for Dr. Efrati to keep innovating, thinking about the future so his patients can process the past.

Doane said, “Some people are gonna listen to this and say it sounds too good to be true.”

“Yeah, I know,” said Negrin. “But it’s fact.”

CBS News

For more info:

Story produced by Sari Aviv. Editor: Ed Givnish.

See also: